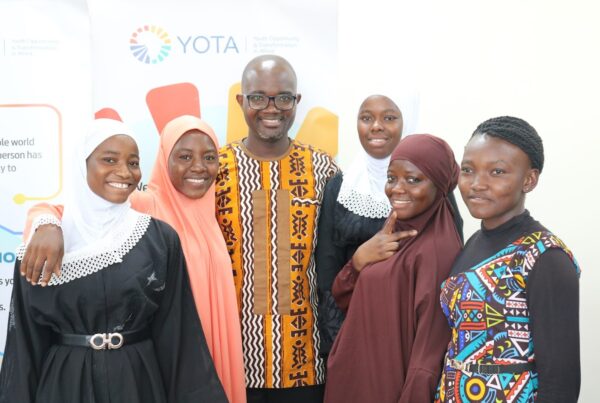

By Emmanuel Edudzie

Executive Director, YOTA.

There is widespread euphoria among Ghana’s youth following the return to power of President John Mahama. His administration faces a generational imperative: to integrate young people into national development strategies and empower them as drivers of economic and social progress.

The vision for youth within John Mahama’s administration reflects the president’s commitment to transforming the lives of young Ghanaians. The manifesto outlines policies, including the creation of a separate ministry for youth development, the introduction of a 24-hour economy strategy, and initiatives to enhance skills development.

However, the true challenge lies in turning these into tangible results, through strong institutional framework and strategic partnerships.

Key policies

The creation of a dedicated ministry for youth development is part of the plan. By providing a centralised authority for youth affairs, the ministry aims to coordinate cross-sectoral policies and ensure that youth concerns receive the attention they deserve.

Past ministries indicate that their success depends on clearly defined mandates, sustainable funding and inclusivity. Without these, such institutions risk becoming bureaucratic entities that fail to deliver tangible outcomes.

Learning from Rwanda, New Zealand and others, Ghana could integrate youth representatives into the ministry’s governance structure to ensure that policies remain relevant to the needs of young people.

Establishing an independent monitoring, evaluation and learning unit within the ministry can ensure that programmes are tracked rigorously. Annual progress reports, made publicly available, will enhance transparency and build trust. Disaggregated data by gender, location and socioeconomic status will help identify gaps and inform targeted interventions.

Another initiative is the promotion of a 24-hour economy, which seeks to address unemployment and boost productivity by encouraging businesses to operate around the clock.

“Ghana must prioritise digital inclusion by establishing regional technology hubs, expanding internet access and partnering with global tech companies.“

While this policy has potential, it must be approached cautiously. In contexts such as the Philippines, where 24-hour operations in industries like outsourcing have created jobs, challenges such as worker exploitation and unsustainable working conditions have also emerged. Ghana must ensure that this initiative is underpinned by labour protection and incentives that encourage businesses to adopt ethical practices.

The Digital Jobs Initiative and National Apprenticeship Scheme addresses the need to equip young people for a rapidly evolving global economy but must go beyond training to include pathways for employment and entrepreneurship. Ghana must prioritise digital inclusion by establishing regional technology hubs, expanding internet access and partnering with global tech companies.

In countries such as Germany, the dual education system pairs apprenticeships with formal education, ensuring that young people gain practical skills while receiving qualifications.

Finally, the manifesto highlights inclusive governance and gender equity as key pillars of its youth agenda. While the commitment to quotas for youth representation in decision-making bodies is laudable, this must be meaningful rather than symbolic. Tokenism undermines the spirit of such initiatives and erodes trust among young people.

Recommendations for policy success

To ensure the effective implementation of its youth agenda, the Mahama administration must adopt a strategic and evidence-based approach. The following recommendations draw on successful youth policies from other countries and youth programmes of international organisations, providing a roadmap for achieving lasting impact.

1. Sustainable and diversified funding

To avoid lack of funding pitfalls, Ghana should look to the example of Singapore, which has its own $100m youth body and sources funding from the government and private sector.

2. Coordination

Youth development is not the sole responsibility of a single ministry; it requires a coordinated effort across government. South Korea’s presidential committee on youth serves as a model for aligning youth policies across sectors such as education, health, and employment. Ghana should establish an inter-ministerial task force chaired by the ministry for youth development to ensure coherence in policy implementation.

3. Targeted and inclusive programming

Inclusivity must underpin all youth policies to address disparities in access to opportunities. Canada’s youth policy demonstrates how targeted programmes for indigenous youth, young women, and marginalised communities can create equitable outcomes. Ghana should adopt a similar approach, tailoring its interventions to the specific needs of rural youth, young women, and persons with disabilities. Affirmative action initiatives, such as scholarships and mentorship programmes, can help bridge gaps in education and employment.

4. Global partnerships

Youth development is a global challenge that benefits from shared solutions. Ghana should actively seek partnerships with the United Nations, African Union, the Commonwealth, and other multilaterals to access resources and expertise.

The Mahama administration has a unique opportunity to reshape the nation’s approach to youth development. By strengthening institutions, ensuring sustainable funding, promoting inclusivity, and embracing innovation, Ghana can set a new standard for youth-focused governance.

This article was originally published on TheAfricaReport.com. Read the original article here